BLOG

Understanding German Wine Classification

Valerie Kathawala

Regions and Producers

A new German wine law requires coming to grips with not one complex system, but three.

German wine classification is vexing: impeccably precise yet notoriously inscrutable — and bifurcated at that. The good news? Germany's national classification system was recently reformed to improve clarity and transparency. The bad? Those reforms do not take full effect until 2026. So, for now, students of German wine must master not one complex classification system, but three. With all this in mind, here is a short guide to the long story of how Germany classifies its wines. Strap in!

System One: The 1971 Wine Law — “Ripeness Rules”

For most of the 20th century, in a marginal region like Germany, the essential question was: How ripe can grapes become each short, cool vintage? German wine classification was set up to reward growers who achieved peak ripeness. Before climate change, this made a certain sense. Not only were the ripest grapes capable of producing wines with the most sugar or alcohol content, but they were also more likely to have reached full physiological ripeness of acids, tannins, flavor and aroma precursors.

German legislators enshrined this paradigm in the 1971 German Wine Law. It pointedly pinned quality to sweetness or potential alcohol but brushed aside terroir and the elements of viticulture and vinification — historic sites, yields, additions, élevage — which contribute to the precise expression of terroir.

The 1971 law set up classifications for Germany’s basic wines, Qualitätsweine, or “quality wines,” and Prädikat wines. These wines “with specific attributes” were required to meet increasingly selective criteria, mostly ascending ripeness levels:

Kabinett (“reserve”) wines, made from fully ripened grapes picked at normal harvest times.

Spätlese (“late harvest”) wines, made from even riper grapes picked at a later stage of harvest.

Auslese (“select harvest”) wines, indicating rigorous selection of very ripe grapes.

Beerenauslese (“berry select harvest,” or BA) wines, made from individually selected, hand-picked, overripe berries usually infected by noble rot.

Trockenbeerenauslese (“dry berry select harvest”, or TBA) wines, made from individually hand-selected grapes that are overripe, almost raisined, and typically infected by noble rot.

Eiswein (“ice wine”) made from grapes of BA quality, harvested and pressed while naturally frozen at a minimum temperature of -19℉/7℃.

Just to keep things interesting, within the first three Prädikate, a German winemaker can choose to ferment a wine to full dryness and label it Kabinett Trocken, Spätlese Trocken, or Auslese Trocken. But the trend is to use Prädikate only for sweet wines.

System Two: The VDP and Terroir–Based Classification

The complexity and obfuscation of the 1971 classification drove many consumers and producers to despair.

Perhaps none more so than the VDP — Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter. Over time, this prestigious, private association of roughly 200 German growers recognized that the national classification system failed to address changes in taste and climate. Both had begun to favor the production of dry wines. Moreover, the national system had all but erased the identity of Germany’s most acclaimed vineyards.

So, in 2002, with one eye on Burgundy, the other on restoring the prestige and marketability of top German wines, the VDP rolled out its own terroir-based classification system. The VDP’s prominence meant that its quality hierarchy gained widespread acceptance as a second, parallel system of classification — albeit only usable by its members.

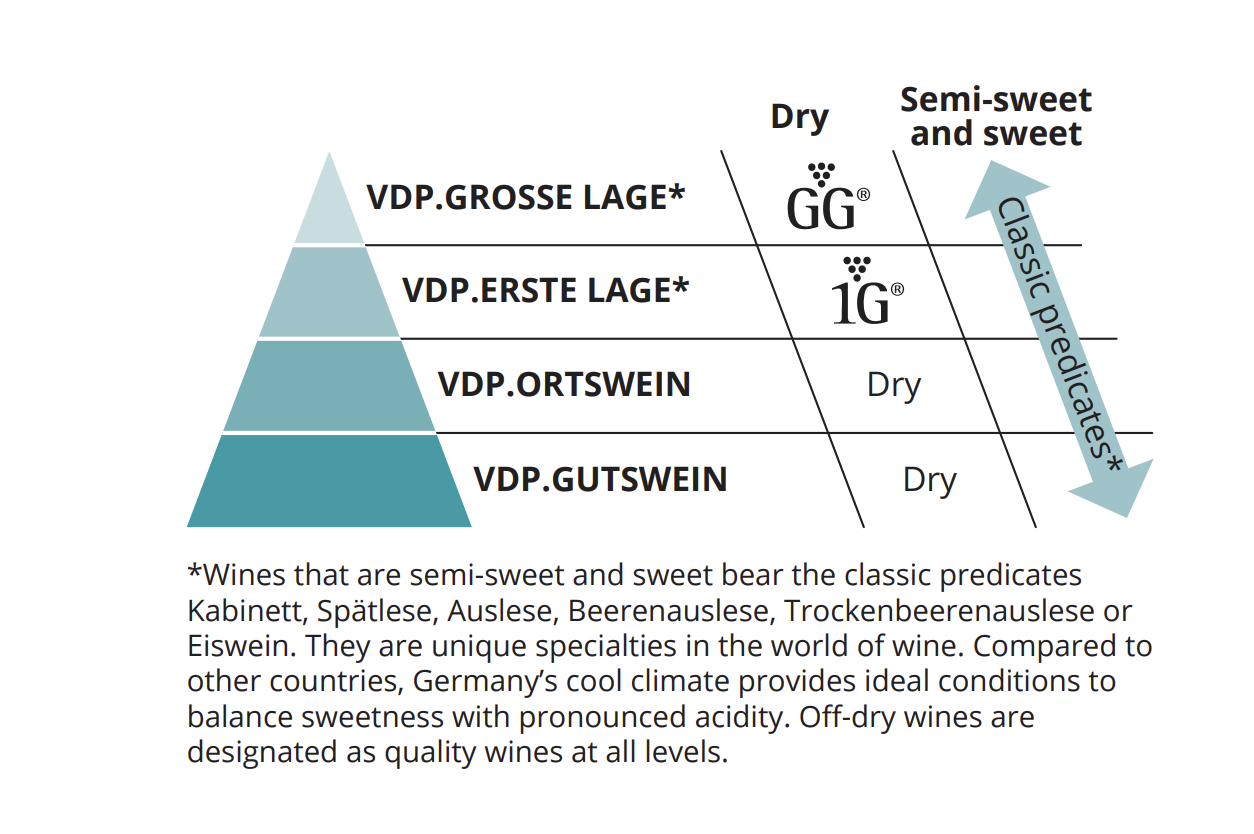

Today, its four-tier classification structure looks like this:

Source: https://www.vdp.de/en/the-wines/classification

All four tiers are for dry wines. Specifications include:

VDP.GUTSWEIN (estate level) from estate-grown grapes, with maximum yields of 4.5 tons/ac or 75 hl/ha

VDP.ORTSWEIN (village level) from top sites from a single village, with the same yield limits as for VDP.GUTSWEIN

VDP.ERSTES GEWÄCHS (“premier cru”) sourced from recognized Erste Lage (“premier cru”) sites; maximum yields are 3.6 tons/ac or 60 hl/ha

VDP.GROSSE GEWÄCHS (“grand cru”) sourced from recognized Grosse Lage sites; maximum yields are 3 tons/ac or 50 hl/ha.

The VDP also has a separate classification for Sekt, or traditional-method sparkling wine:

VDP.Sekt (minimum 15 months on lees, 24 months in bottle)

VDP.Sekt Prestige (36 months on lees, 36 months in bottle)

Note that the VDP prefix and all-caps rendering are part of the VDP brand. Also, VDP members may still classify their sweet wines using the Prädikat system.

System Three: The 2021 German Wine Law — Origins Matter After All

It turns out that having two parallel, complex systems was not the way to win over converts to German wine.

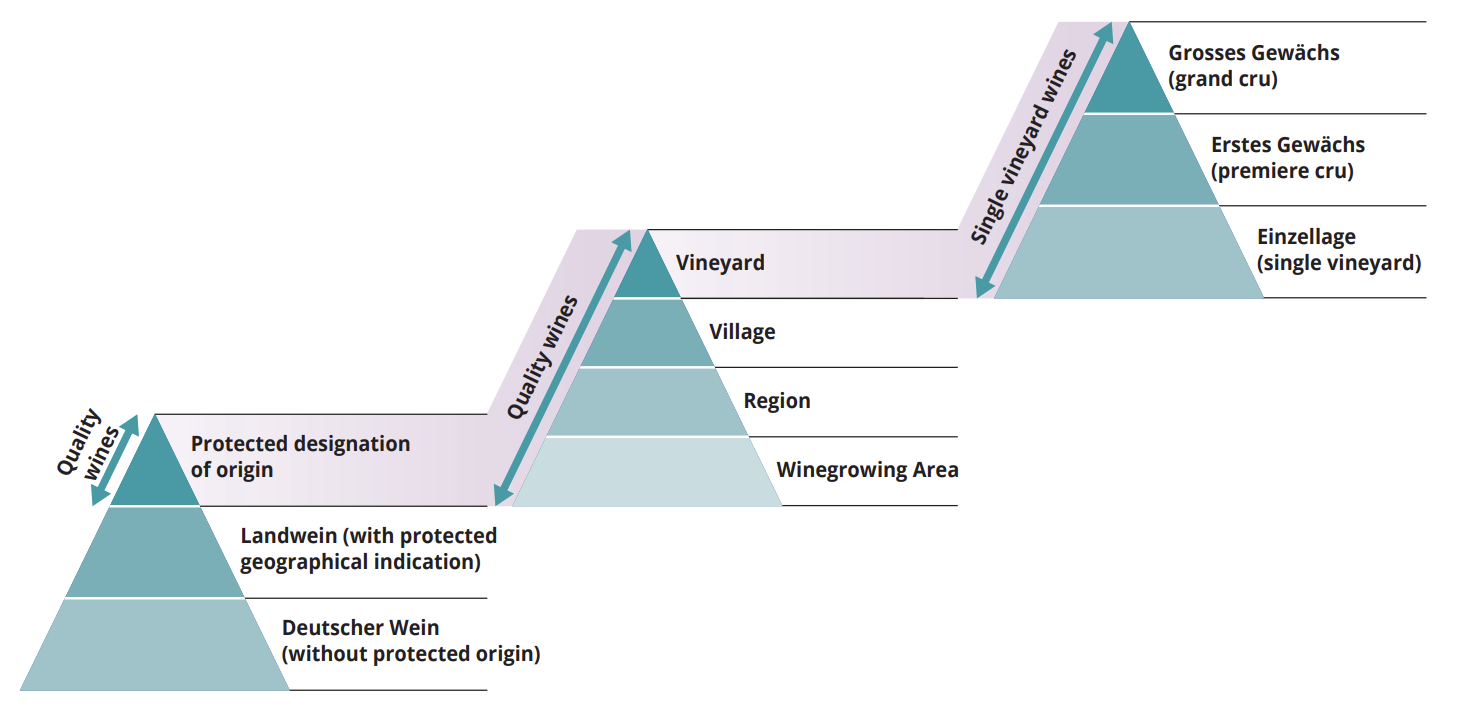

In 2021, the German government finally recognized this. Germany got a new wine law — and, with it, a new classification system. Under the motto “The smaller the origin, the higher the quality,” German wines are now largely classified by terroir, not ripeness.

(If you note striking parallels with the VDP’s classification, you are not alone. See Steven Sidore’s analysis of the new law’s “winners and losers” in TRINK magazine.)

The kicker? The new law and classification do not take full effect until 2026. Up to and including vintage 2025, German wines may still be labeled under the old rules and kept on the market. This means that for the next year, students of German wine will need to retain a grasp of the 1971 classification, the VDP classification and the 2021 classification.

First, the good news! The 2021 classification does not change the existing Prädikate. The additional indication of Prädikate is still allowed by the 2021 wine law for all categories of Qualitätswein (except Erstes Gewächs and Grosses Gewächs).

What does change is that quality is now assessed by narrowing geographic specificity. Again, “the smaller the origin, the higher the quality.”

Deutscher Wein (German Wine)

The new classification starts here, with Germany’s most basic wine category. Requirements include grapes grown only in Germany, minimum alcohol by volume of 8.5% and maximum of 11.5% for white or rosé wine and 12.5% for red wine, with minimum total acidity of 3.5 g/l. No Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) or Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) is indicated.

Landwein (Country Wine)

At least 85% of the grapes for a Landwein must originate in a given Landwein region — one of 26 in Germany — as stated on the label. Landwein is typically Trocken (dry) or Halbtrocken (off-dry). Minimum alcohol by volume is set at 8.5% and maximum of 11.5% for white or rosé wine and 12.5% for red wine (after chaptalization, if applicable). This is equivalent to the EU’s PGI. Despite the rising popularity of this category among natural wine producers, less than 3.5% of German wine is classified as Landwein.

Qualitätswein (Quality Wine)

The vast majority (60-80%, the share depends on the vintage) of German wine is classified as Qualitätswein. These wines must originate entirely from a single German Anbaugebiet, or wine region one of 13 in Germany — and the region must be declared on the label. Wines can only be made from legally permitted grapes and must reach a minimum alcohol content as prescribed for the region. Among the notable provisions of the 2021 wine law, the term Qualitätswein can now be accompanied or replaced by the term geschützte Ursprungsbezeichnung (g.U.), or PDO combined with the name of a winegrowing area.

Still here?

Qualitätswein is now subdivided into four narrowing tiers of origin. These are: Anbaugebiet (wine region), Region or Bereich (district), Ort (village), and Lage (vineyard). Lage sits at the apex of this pyramid.

The 2021 law then goes further, splitting Lage into three rising quality levels:

Einzellage (single vineyard) wines must reach a certain ripeness level; further specifications are set regionally.

Erstes Gewächs (premier cru) are white or red wines produced from a single variety identified as traditional and characteristic of a particular region. Yields may not exceed 3.6 tons/ac or 60 hl/ha on flat land, 4.2 tons/ac or 70 hl/ha on steep slopes. Potential alcohol must be at least 11% and come from a declared vintage and site or parcel. The wine must be vinified dry and pass a sensory evaluation by an official tasting committee. Erstes Gewächs may not be released before March 1 of the year following the vintage.

Grosses Gewächs (grand cru) are the pinnacle. Only white and red wines produced from a single variety identified as traditional and characteristic of a particular region qualify as “GG”s. Manual harvest is required. Yields are capped at 3 tons/ac or 50 hl/ha. Potential alcohol must be at least 12%. The wine must come from a declared vintage and a particular site or parcel. The wine has to be vinified dry and pass a sensory evaluation by official tasting committee. Grosse Gewächse may not be released before September 1 of the year following the vintage if white and June 1 of the second year after the vintage if red. The new law goes so far as to allow parcels within a single vineyard to be stated on a wine’s label, provided that these Gewannen, or cadastral vineyards, are entered in an official vineyard register.

What comes next?

If you’ve made it this far, you’re already well on your way to understanding the most complicated aspect of German wine. Why not take the — easy — next step toward mastery by enrolling in the German Wine Scholar program? This certification course launches in 2025. Click here to learn more.